Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Lionfish: a very spiny problem!

For anyone who has been diving in the Caribbean in the last few years, you have probably heard of the lionfish problem. Having taught marine biology & conservation in the Caribbean for several years, it’s a question I get asked about a lot. This blog explains some of the facts about lionfish and what we can do to help our reefs:

- Where should they be?

- How did they get into the Caribbean?

- What is all the fuss about?

- What you can do to help the reefs?

Where should they be?

Lionfish are a beautiful predatory fish, native to the Indian and Pacific Oceans and the Red Sea.

In their native habitat the lionfish is great to observe and photograph. They are not very common as they have natural predators that keep population down and in balance with the other reef fish (Density/hectare in the Pacific is ~20).

How did they get into the Caribbean?

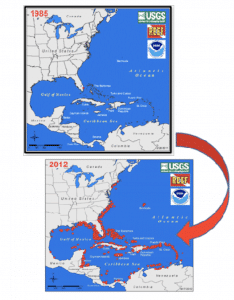

Unfortunately since 1992, two species of lionfish (Pterois volitans & Pterois miles) are now found in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, where they are an invasive species. The theory is that captive lionfish were released or escaped off the coast of Florida and the population has spread. Lionfish established themselves in the Caribbean in less than 3 years and range from North Carolina to South America including the Gulf of Mexico. From a few individuals in 1992 the population has now spread out of control to become a major problem in the ecosystem (Density/hectare in Caribbean ~398 in 2012).

What is all the fuss about?

Why are lionfish an issue?

To understand the issue, we first need to know a bit about the fish.

Lionfish biology:

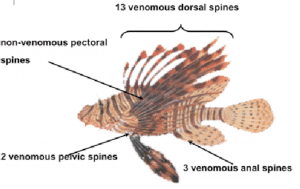

They have venomous tissue within their spines for protection and are generalist carnivores. Adults can grow up to 42cm and have a lifespan of 5-10 years. They become sexually mature in less than a year and spawn in pairs. Females can release 30,000 eggs at one time. Enclosed in a mucus layer, the eggs float to the surface. In a few days the mucus dissipates and the eggs are released to be dispersed by ocean currents.

Habitat & ecology

Lionfish inhabit all marine habitat types (reefs, lagoons, mangroves, sea grass beds, sand patches and artificial substrates) and can handle tropical temperatures all the way down to 10°C. They can also live at a huge range of depths (from shoreline to over 300m or 1000 feet), though they tend to be territorial, so may remain in the same area for up to 7 months. They appear to be attracted to cleaning stations.

So why are they a problem?

Lionfish have no natural predators in the Caribbean. The density per hectare of invasive lionfish is around 20x higher than in their native waters. They consume over 70 species of fish and many invertebrate species and can eat prey up to half their body length (basically they can eat pretty much anything!). This makes them top predators along with sharks, rays and groupers. By colonising mangroves and sea grass beds they pose a major threat to juvenile fish (this is where lots of baby fish live until they are big enough to survive out on the reef).

On heavily invaded sites, lionfish have reduced their fish prey population by up to 90% and continue to consume native fishes at unsustainable rates. Many reefs have been decimated of the native reef fish as the lionfish consume until supply of fish has run out. Once the food has run out, lionfish can survive for 12 weeks with no food, so can move on to other feeding grounds. Reefs without fish don’t function, so the coral also starts to suffer.

Invasive lionfish reproduction occurs throughout the year and as frequently as every 4 days (whereas native Indo-Pacific lionfish breed only once a year!). This means an invasive female lionfish can lay over 2 million eggs/year in the Caribbean. And unlike in the Indo-Pacific, many of these eggs will survive to adulthood. This means the populations are increasing at a phenomenal rate (700% in 4 years!).

Where lionfish containment programs operate, the deep dwelling fish can be very hard to get to in order to kill or capture. So lionfish pose a threat to the integrity of the reef food web and can have wide reaching impacts on commercial fisheries, tourism, and overall coral reef health.

What you can do to help the reefs?

Educate others and spread awareness of lionfish.

EAT THEM!! They are a delicious delicacy (see RECIPES below!). Also eating this fish reduces pressure on fish stocks of native species.

Encourage local restaurants to serve Lionfish and promote consumption by community members.

We need to be the main predator and keep dive sites as free of Lionfish as possible. Though we cannot get all of them, reducing the numbers on the coral reef and shallow water can really help native fish species and coral health.

Lionfish removal:

Spearing lionfish is quick and safe if done properly (Hawaiian Slings can be used very effectively). A tube container is recommended to store captured fish.

Many marine park authorities and islands have licensed spearing lionfish as local removal efforts can significantly reduce lionfish densities and subsequent impacts. Efforts are invaluable for supporting other conservation initiatives like management of marine protected areas, pollution control and fish stock rebuilding in order to help our reefs.

Try our favourite Lionfish Recipes! To see them click here.

- Island Lionfish Fry

- Lionfish Ceviche

- Lionfish Coconut Curry

- Coconut Lionfish with Spicy Mango Dip

- Marinara Lionfish Spaghetti

- Lionfish Tacos with Street Corn and Salsa

- Cajun Spiced Lionfish Fillets with Mango Salsa

- White Wine Lionfish

- Lionfish Sanganaki

- BBQ Lionfish: Kebabs and Parcels

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Shark Trust Expedition Dives in The Bahamas

In our last blog we talked about why the Shark Trust had been in The Bahamas in December. With the underwater part of the expedition focused on getting 360 footage for a new immersive shark experience, OneOcean360: A Shark Story, that will be launched later this year. Now, let’s tell you a little bit more about the diving we did, along some more surprising shark sightings!

The Shark Trust 3-island expedition, which was fully funded and supported by the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism, started in Nassau. And we were booked to do 2 days of diving with Stuart Cove’s Dive Bahamas. We packed in as much diving as possible, leaving as soon as the boat was loaded and returning as the sun was setting, covering 7 dive sites over the 2 days, with a mix of reef and wrecks to ensure we got as much varied footage as possible.

Pumpkin Patch saw us hang out with a very chilled turtle while Caribbean Reef Sharks swam along the drop off beside us. We visited a “wreck” structure built for the filming of a James Bond film that was now covered in bright corals and home to a multitude of reef fish. Steel Forest saw us diver some “proper” wrecks that have been sunk alongside each other. Glass fish swirled under overhangs and larger fish hung motionless in the wheelhouse. Southern Sting rays lay buried in the sandy seabed alongside. Our final dive of the day, as the sun started to set, Ridges, combined a reef and wreck where we caught a fleeting glimpse of a Bull Shark as we ascended the line. It was a great diving day that gave us the perfect introduction to the underwater world of The Bahamas.

Our second day was going to focus on getting close up footage of Caribbean Reef Sharks on both wrecks and reef. The Ray of Hope and Big Crabs wrecks are perfect for this. With our guide placing bait boxes inside the wrecks to attract the sharks, and with our cameras setup on the wreck structure, we could back away and let the sharks do their thing without us disturbing them or being in the 360 filming frame. With clear water and plenty of sharks, the footage we came away with in pretty striking.

Next stop: Bimini. Great Hammerhead Sharks are the number one attraction here. And we were able to join Neal Watsons Bimini Scuba for a 2-tank dive with these magnificent sharks, along with the Nurse Sharks that like to join in with the experience. But we were also able to snorkel with juvenile Lemon Sharks in the Mangroves, see Bull Sharks and spotted eagle rays from a submarine experience and from the dock side. Our second day of diving saw us dive the SS Sapona wreck and then experience the Caribbean Reef Sharks on the reef. Bimini really does allow you to pack in a load of shark and ray experiences in a short space of time.

Finally, we headed to Grand Bahama. Whilst much of our time was spent above the water meeting people working to conserve different marine habitats (watch this space for more information on this) – we did manage to squeeze in a couple of dives on the reefs here and were delighted to see both Caribbean Reef Shark and Southern Stingrays on both. Our final shark and ray experience saw us take a tour to Sandy Cay with Keith Cooper. We were able to get footage of stingrays, lemon and blacktip reef sharks on the seagrass and over the sandy seabed. Sometimes just in ankle deep water.

If you are heading to the Go Diving Show – then you will be able to see a short 360 film, using our VR headsets, that shows many of these experiences. Please come and say hello to the Shark Trust team on the Diverse Travel stand (340). We will also be on The Bahamas stand twice a day to chat to people about our experiences on the islands. And Diverse travel will have special offers on travel to The Bahamas should you want to follow in our fin-kicks.

To find out more about the work of he Shark Trust and how you can support us, visit out website www.sharktrust.org

Blogs

Evolution of Manatees in Florida

Op-ed by Beth Brady, PhD, Senior Science and Conservation Associate, Save the Manatee® Club

Recent news articles and broadcasts have claimed that manatees are not native to Florida or only arrived on Florida’s west coast in the 1950s. These claims, based on limited anthropological records, point to where manatees were historically exploited by humans and assume that a lack of evidence means manatees were absent from certain areas. However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence—it’s like looking for stars in the daytime; just because you can’t see them doesn’t mean they’re not there. Moreover, genetic and fossil evidence indicate manatees have been present in Florida for the last 12,000 years.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), which manages Florida manatee populations, has created a manatee timeline highlighting key dates and notable information about manatee presence in Florida (https://myfwc.com/education/wildlife/manatee/timeline/). Historical records suggest that manatees have been observed in Florida as far back as the 1500s, with some details presented by the Florida Fish and Wildlife timeline aligning with evidence presented in the publication.

Manatee species, such as the African manatee and the Antillean manatee, continue to be poached by humans (Marsh et al., 2022). As a result, these species are difficult to observe in the wild and may adapt by foraging at night to avoid human encounters (Rycyk et al., 2021). This behavior could help explain why historical Florida manatee populations that were hunted by humans are absent from middens and rarely mentioned in historical accounts.

Further, the publication only briefly touches on the paleontological record and genetic evidence, which indicate that manatees have existed in Florida for a much longer period. Fossil and genetic evidence reveal a rich history of manatees in Florida. Manatees belong to the order Sirenia, which includes the Amazonian, African, and West Indian manatee species. While Sirenian fossils have been found globally, only Florida and the Caribbean contain specimens from every epoch over the past 50 million years (Reep and Bonde, 2006). The modern manatee, as we know it, emerged in the Caribbean about 2 million years ago (Domning, 1982).

The evolution of manatees during the Pleistocene epoch provides valuable insights into how environmental changes shaped their distribution and genetic diversity. During the Pleistocene epoch (2.59 million to 11,700 years ago), there were roughly 20 cycles of long glacial periods (40,000–100,000 years) followed by shorter interglacial periods lasting around 20,000 years. At the start of these warmer periods, Caribbean manatees migrated northward with the warming waters (Reep and Bonde, 2006). Water currents and thermal barriers isolated these manatees from populations in Mexico and the Caribbean, leading to genetic divergence. Fossil evidence indicates that Trichechus manatus bakerorum lived in Florida and North Carolina about 125,000 years ago but did not survive the last glacial period, which began 100,000 to 85,000 years ago (Domning, 2005). This subspecies was eventually replaced by modern Florida manatees.

This evolutionary theory is further supported by genetic evidence. Research indicates that Florida manatees trace their evolutionary origins to Caribbean ancestors that migrated northward over the past 12,000 years (Garcia-Rodriguez et al., 1998). A 2012 study by Tucker et al. reinforces this theory, showing higher genetic diversity in manatees on Florida’s west coast compared to those on the east. Over time, core populations migrated northward, with some groups moving south and east along the Florida coastline before heading north along the Atlantic. This migration pattern left the west coast population with greater genetic diversity, while the east coast population retained only a smaller subset. These findings suggest that the founding population of Florida manatees—arriving approximately 12,000 years ago—originated along Florida’s southwestern coast, which became the center of the state’s manatee population (Reep and Bonde, 2006). The process of vicariance further supports this hypothesis; as geographic and ecological barriers emerged, they likely isolated the Florida manatee populations from their Caribbean ancestors. This isolation likely limited migration back and forth between regions, fostering the establishment of local populations in southwestern Florida.

Manatees are not only a cherished symbol of Florida’s natural heritage but also a species with deep evolutionary and historical ties to the region. In sum, despite recent claims questioning their nativity, extensive fossil and genetic evidence confirms that manatees have been present in Florida’s waters for thousands of years, with ancestors dating back over 12,000 years. We agree with the authors of the published article that protecting these iconic creatures and their habitats is essential to preserving Florida’s unique ecological identity for future generations

Beth Brady is the Senior Science and Conservation Associate at Save the Manatee Club whose work focuses on manatee biology and conservation. She has her PhD from Florida Atlantic University and her Master’s in Marine Science from Nova Southeastern University.

-

Gear Reviews2 months ago

Gear Reviews2 months agoGear Review: SurfEars 4

-

Marine Life & Conservation3 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation3 months agoPaul Watson Released as Denmark Blocks Japan’s Extradition Bid

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoHumpback Mother and Calf Win Underwater Photographer of the Year 2025

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoGo Diving Show 2025 Exhibitor Showcase

-

News2 months ago

News2 months ago2-for-1 tickets now available for GO Diving Show

-

Blogs3 months ago

Blogs3 months agoJeff Goodman Launches Underwater Moviemaker Course with NovoScuba

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoDive into Adventure: Limited Space Available for January Socorro Liveaboard Trip with Oyster Diving

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoFilming 360 in The Bahamas